The Veritas Custom Bench Planes

To Chipbreak or Not to Chipbreak: frog angle choice and bevel up performances

It is time to decide on the frog angle. Essentially, if you work with wood that threatens to tear out, then you must decide whether setting the chipbreaker is worth the effort. If not, then either you will choose a suitable angle for the frog, or use a BU plane with a high cutting angle.

I have used BU planes for smoothing for a good number of years. The reason is simply that they perform so well on highly interlocked timber. BU planes enable one to create a high cutting angle, and it is this that succeeds in defeating tearout. The other advantage to a BU plane is that it has a low centre of effort. The force vector focuses the energy efficiently. I have long argued that, angle-for-angle, a BU plane require less effort to push and offer more feedback than a BD plane with a high centre of effort.

There is a downside to BU planes for me. This may not affect others - it depends on how you sharpen your blades.

To achieve a high cutting angle, the bevel angle needs to be high. For a 60-degree cutting angle, the bevel needs to be 48 degrees (assuming that the bed of the BU plane is 12 degrees). While this, in itself, is not difficult to do, adding a camber to a high bevel angle is a more work since it requires that a significantly greater amount of steel is removed relative to a similarly thick blade with a low primary bevel (of say 25 degrees). While there is a work-around, this requires the use of a honing guide to create a high micro secondary bevel on a low primary bevel. This is not an issue if you are someone who hones with a guide. However, I prefer to freehand sharpen.

Consequently, for even years longer I have used planes with high angle beds, which use blades with primary angles that I might freehand hone. Planes such as HNT Gordon figure prominently since they have a low profile and a lowered centre of effort. I built many razee woodies with single irons and high angle beds.

I have not been a big fan of Bailey-style planes with high angle frogs. I have a bronze LN #4 ½ and a bronze LN #3, both with 55-degree frogs. These are very fine planes and perform well; however, the high cutting angle in a plane with a high centre-of-effort, requires greater-than-average effort to push. Waxing the sole helps considerably. Nevertheless, I have swapped out the frogs on both for ones of 50 degrees – again, seen to be a compromise between straight-grained wood (no chipbreaker needed) and interlocked wood (use the chipbreaker).

The question now is, “what is the better frog angle for someone who is comfortable using a chipbreaker?”. Does 50 degrees perform well enough without a chipbreaker? Can we go lower than 45 degrees if using the chipbreaker?

To answer these questions I have 50- and a 42-degee frogs.

Why 42 degrees? A couple of reasons ... Firstly, with a 30 degree bevel, this offers the same clearance angle as a BU plane (i.e.12 degrees), which is within safe margings. Secondly, it is expected that the lower the cutting angle, the greater the slicing action, and the smoother the final surface (particularly on soft woods). Thirdly, I recall Warren mentioning that his preferred smoother was a Stanley #3, with the frog modified 42 degrees. Fourthly, I had already achieved excellent results using the 40-degree frog (plus chipbreaker) in the jointer, and the risk appeared smaller as a result. The stars seemed to be in alignment, so I ordered a 42-degree frog for the #4.

Plane configurations:

(1) #4 Custom Veritas with 42-degree frog and set chipbreaker.

(2 and 3) #4 Custom Veritas with 50-degree frog, both with set- and un-set chipbreaker.

(4 and 5) #4 Stanley Bedrock (45 degree frog), using a custom M4 blade, both with set- and un-set Veritas chipbreaker.

(6) Veritas BU Smoother with 62 degree included angle.

All Veritas blades used were PM-V11.

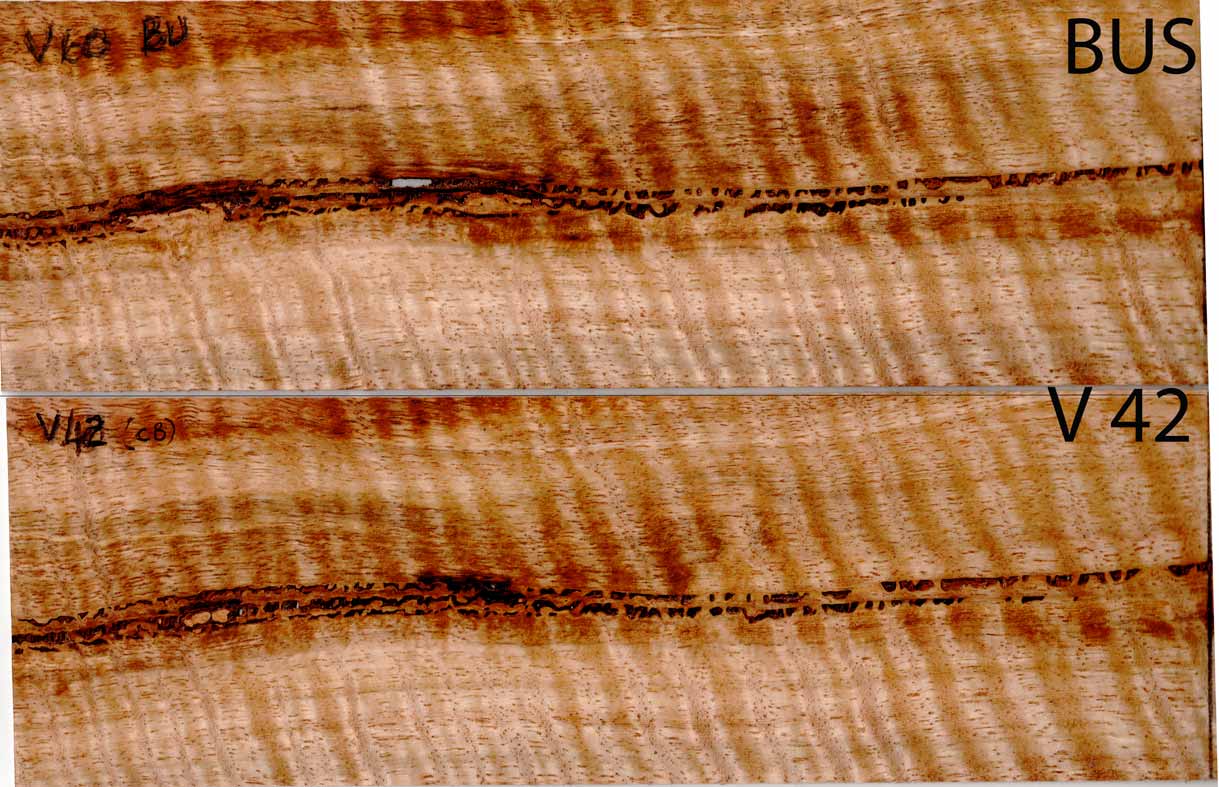

The wood used for the test was a section of West Australian Fiddleback Marri. I once described this as “beautiful firewood” …

The reason for this choice was simply that this would truly test the plane configurations.

Above is the single board that would be used throughout.

Above is the edge grain, which reveals that the grain is highly interlocked. It really makes no different which direction the board is planed!

Before a plane was used, the board was lightly run over my Hammer power jointer with shelix head. This ensured a flat (sic!) playing field for all planes. After each plane had smoothed the side, this was bandsawed off as a permanent record.

Below: Stanley Bedrock with configured chipbreaker …

Below: Custom Veritas with 42-degree frog and configured chipbreaker …

Below: Veritas BUS with 62-degree included angle …

Below: Custom Veritas with 50 degree frog and unconfigured chipbreaker …

Below: Custom Veritas with 50-degree frog and configured chipbreaker …

Below: Stanley Bedrock with unconfigured chipbreaker …

Below: The slices of planing efforts. Note that one board contains the Stanley/No chipbreaker on one side and Custom Veritas 50/configured chipbreaker on the other side (as I ran out of board to use at the end) …

Half of each board was given one coat of oil (Ardvos Universal Wood Oil), while the other was left bare wood.

I invited family, friends and neighbours to rate the finishes in order, both bare wood and oil finished.

So .. what was the upshot?

In order of best to worst:

Veritas Custom 42-degree frog with chipbreaker.

Veritas BUS (62 degree included angle).

Stanley Bedrock (45 degree frog with chipbreaker).

Veritas Custom 50 with chipbreaker.

Veritas Custom 50 without chipbreaker.

Stanley Bedrock without chipbreaker.

It is noted that there was not a lot of difference between the first four boards. An oil finish does tend to obscure some of the fine detail that is apparent in the unoiled boards, but then it also brings out other detail (“makes the grain pop”). Certainly, the first three stood out as a group, with the fourth just a tad behind them.

By contrast, the Bedrock sans chipbreaker caused considerable tearout. The difference between it and using the chipbreaker was night-and-day. The Custom Veritas 50, also without chipbreaker, produced a reasonable finish, and it was only with fingertips that one could recognize the fine tearout that existed.

The low 42 degree frog gets my vote for the unoiled finish. With the unfinished boards, the difference between the first two ranked planes was partly evident by feel and sight – the lower angled plane felt slightly smoother and had a slightly better clarity to the surface. The Fiddleback had a slightly greater 3-D effect. It was as though the valley of the curl was deeper.

When it came to the oiled finish, much of the differences disappeared. My vote still goes to then Veritas 42-degree frog, but I would be happy with either finish.

The Bedrock with closed up chipbreaker performs very nearly as well as the Veritas 42. The unoiled board is below. Viewed independently of the other results, there is no doubt in my mind that the result would be considered exceptionable.

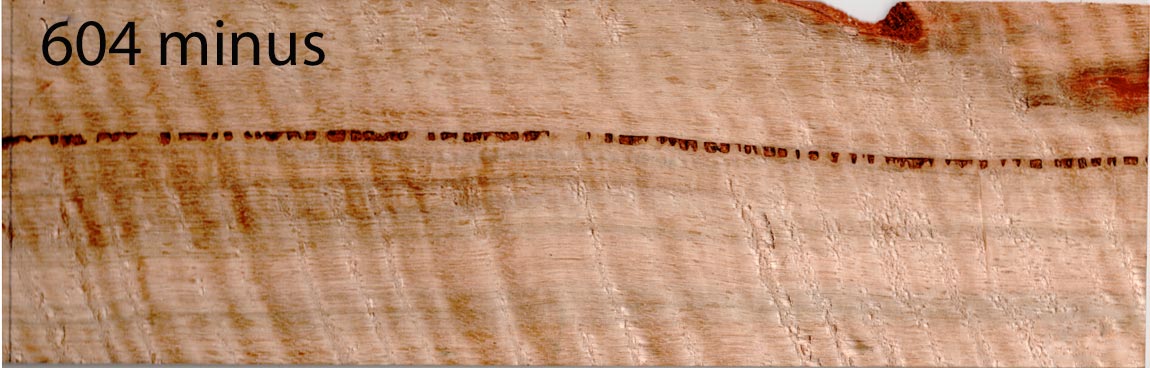

Just how much the chipbreaker can add to the result is seen in the image above of the Bedrock minus the chipbreaker. The tearout is obvious and unacceptable.

Jointing BD versus BU

The BD and BU jointers initially felt very different in the hand. The BU jointer is an incredibly easy plane to use as it has such a low centre of gravity, and it sucks down onto the wood. The BD jointer has a medium centre of gravity, feels solid and offers more feedback that I recall from my Stanley #7. Both the BU and BD planes feel taut and balanced.

Below is the LA Jointer with a Bill Rittner replacement handle and knob. The BD Jointer has the Traditional handle ...

What do I mean by “feedback”. To understand the feedback from the BU jointer you need to imagine a comparison between walking in a pair of slippers and then in a pair of shoes. The slippers are thin and your feet are more sensitive to the surface you are walking upon. Go from a BU Jointer to a high-sided woodie, and you will realise that the planes offer very different experiences of planing/ jointing. The feedback from the BU jointer has little to do with the mass of the plane - instead it seems as if it has more to do with transmission of vibration through the plane's body.

Even when the BD jointer became more familiar, it did not achieve the same direct feedback of the BU jointer. The BU just felt more precise. The gap narrowed some when I switched handles on both to the Standard type. This handle tends to lock in how one can push the plane, and prevents any rocking.

The advantage of the BU plane is that it is just so easy to use. Mine has a 40-degree straight blade (52-degree included angle) for match planing.

The advantage of the BD plane is that I could plane with a 40-degree blade/chipbreaker combination and achieve equally good surfaces on interlocked grain. It could shoot endgrain better than the higher-angled BU jointer.

Final Selections

The #7 Jointer has a 40-degree frog (to be used with chipbreaker), the Standard handle and a Wide knob. The Standard handle has been added to the BU Jointer ...

The #4 Smoother has a 42-degree frog (to be used with the chipbreaker), the Traditional handle and the Wide knob …

Conclusions and Recommendations

It is important to recognise that the wood used in this test is an extreme example of interlocked hell. It served to test the limits of the planes and their separate configurations. Most woodworkers will tend to deal with far more moderate grain, and the differences will collapse into something of an average. On the other hand, these results do demonstrate what may be expected for those times you do work with woods that contain a higher-than-expected degree of interlocked and reversing grain.

The intent of this series of articles has been to help you choose a jointer or smoother by identifying what is important in using one - what works and why.

I think that it is evident that the handle type, and how it is used, is particularly important. I am inclined to suggest the standard Veritas handle if you are starting out or for jointers. This facilitates the plane being pushed forward. There is no reason to create a force vector in any other direction.

For shorter planes, such as a smoother, there is a choice. Again, the straighter Veritas handle will keep many out of trouble, that is, make it less complicated to direct force forward. The forward-leaning Traditional style handle offers greater flexibility – one can rock forward, starting high, then drop the hand to push forward.

Downforce comes through the knob. Since forward drive comes from the handle, the knob is simply used to keep the mouth flat to the surface. For this reason, the flatter-topped, mushroom-shaped knob is the knob of choice.

With regards the frog, if you are a chipbreaker user, then a 40-42 degree choice offers a far greater range: end grain, shooting, interlocked grain, and easier pushing. If you do not plan to use a chipbreaker, and would rather rely on the cutting angle, you have the choice of a BU plane or a BD plane with a frog in the region of 50-55 degrees. A conservative choice is 45-degrees.

It must be mentioned that the Stanley #604-plus-chipbreaker performed superbly. The one used here is a little special insofar as it has a custom blade that held its edge well and a (Veritas) chipbreaker that is easy to set up. Nevertheless, many others report similar results with less tuning. It represents performance-for-value. On the other hand, the performance is rather mundane without the chipbreaker.

By no means do I consider that these are the only insights, and I would love to use these articles as a springboard for discussion on the forum. Please feel free to disagree or agree, but please add your reasons.

I hope that this journey of mine has helped somewhat in preparing you for your own.

Regards from Perth

Derek

January 2015